Review of EnglishCentral in Language Learning & Technology Journal

Language Learning & Technology

Gregory Strong, Aoyama Gakuin University

October 2021, Volume 25, Issue 3 pp. 56–61

ISSN 1094-3501

EnglishCentral

Product Type: a web-based learning platform

Requirements: a mobile device, tablet, or computer; a microphone and speakers

Access: a website with a mobile app from the Apple Store or Google Play syncing other devices so that learners can log on anywhere

Available From: EnglishCentral

Cost: academic or individual rates starting at $8 monthly per student per class for 4 months, $6 for 6 months, and $5 for 12 months. Additional charges for the Go Live! Lessons employing live tutors.

EnglishCentral (EC) is a commercial learning platform (CLP) well-suited to individual learning, to language practice in class, or to integration in a course curriculum. Its website includes many authentic commercials, documentaries, movie trailers, news reports, and speeches that provide the extensive listening and speaking opportunities that are essential to language acquisition. Because educators cannot provide enough classroom time or even suitable resources, a CLP like EC can help bridge the gap. Conveniently accessible for tablets, personal computers (PCs), and smart phones, EC offers a strong pedagogy and its versatile platform enables teachers to conveniently monitor and respond to student efforts.

Founded in Japan in 2008, EC is not well known in countries where English is a first or second language, but it is reaching a growing number of students and educators worldwide. EC incorporates several key hypotheses from contemporary language acquisition research. First, it provides students with extensive exposure to authentic comprehensible speech in real-life contexts. EC also leverages learner motivation through letting students choose their own listening material. Finally, it promotes language acquisition through exposing students to the vocabulary essential to academic or business communication. Students learn of gaps in their vocabulary and create personal word lists that they review through spaced repetition activities.

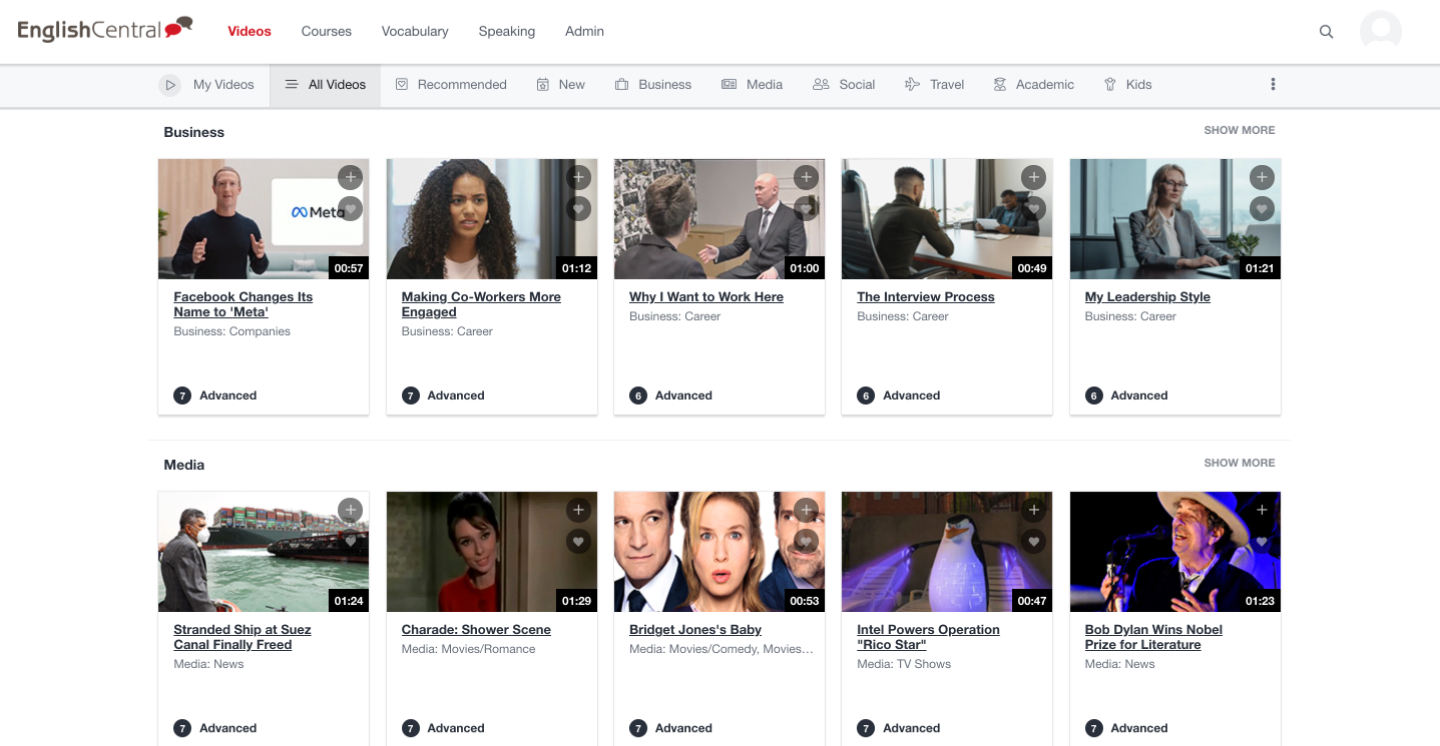

The EC website, which the company sometimes refers to as “a YouTube for language learners”, consists of 15,400 videos that will cover a very wide range of student interests (see Figure 1). Some videos have been obtained through licensing agreements, but most (like Viola Davis’ 2017 Oscar acceptance speech or the big tech CEOs’ recent address to Congress) are in the public domain. These are high interest materials to students of popular culture and of business, while other videos cover such topics as science, travel, and food. They help motivate students to put in the many hours required to develop their listening comprehension and speaking proficiency.

Once they become familiar with the website, students find it easy to navigate it. They can synchronize their phones with other devices such as their PCs by downloading an app from the EC website, so that they can pick up their studies wherever they wish. After logging into the EC website, learners can choose a video from such themes as Business, Media, Social, and Academic, and select the video’s level of difficulty (Beginner, Intermediate, or Advanced). They can control a video’s speed of play, listen to the video multiple times, and consult the video’s transcript. In addition, they can click on any word in the transcript and get a dictionary definition. After watching the video, students complete substitution and sequencing exercises based on the lines that they have just heard, as well as practice pronunciation by repeating these same lines aloud. EC enables students to track the videos that they have watched, the words that they have learned, the lines that they have spoken, and the progress that they have made on their course goals.

Figure 1

The EC Homepage Menu and Toolbar

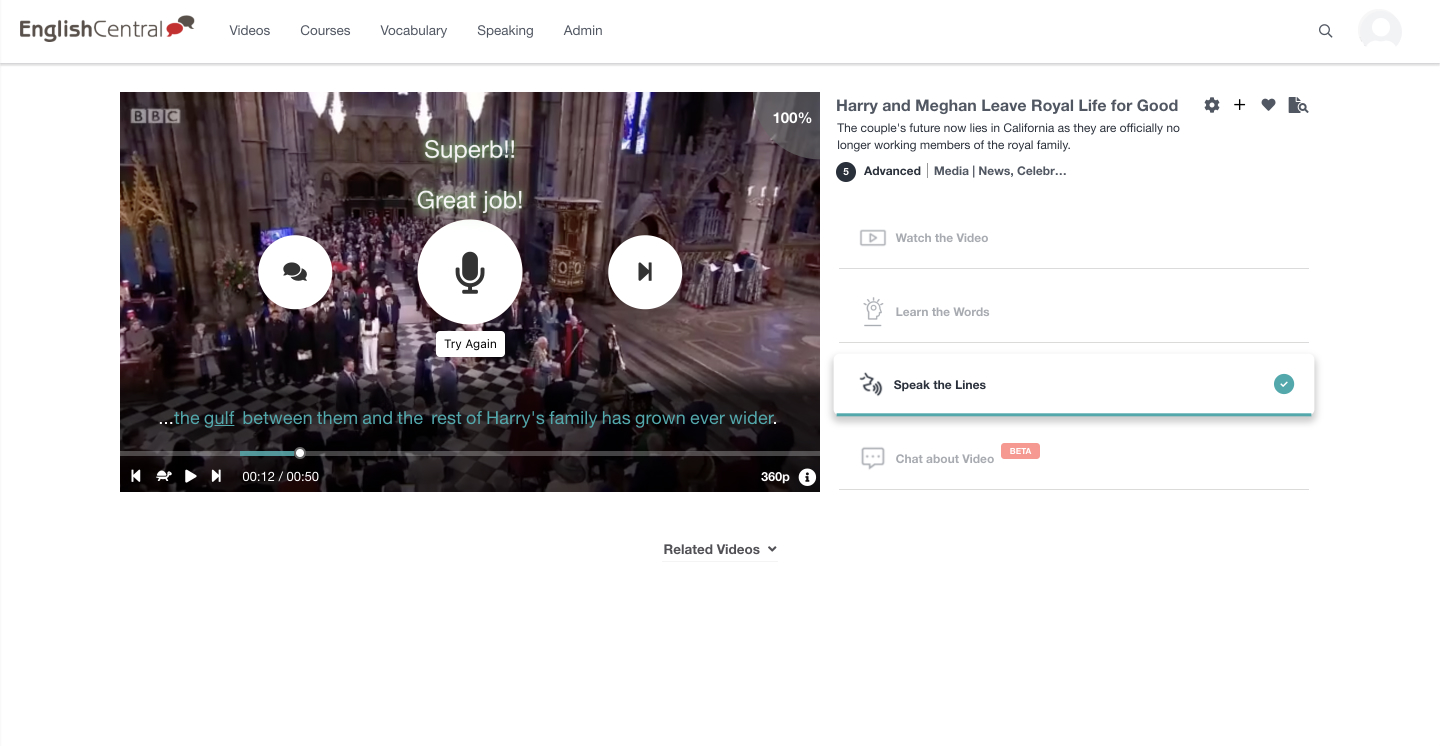

One of EC’s most powerful features is automated feedback on learners’ pronunciation and fluency provided through EC’s trademark IntelliSpeechSM which draws on an expanding database of more than 600 million utterances from EC users worldwide. Students with little experience or opportunity to speak English can try pronouncing a phrase from a video as many times as they wish without worrying about the reactions of their teacher or classmates. Figure 2 shows the feedback given to a student, congratulating the student on good pronunciation. By clicking on an underlined target word, a student can hear the word, repeat it, and view the word broken into its phonemes. Then by pressing the microphone icon, a student can make a recording, hear the recording played back, and receive automated feedback on it. The student also can save the target word for further review.

Figure 2

Speaking Practice

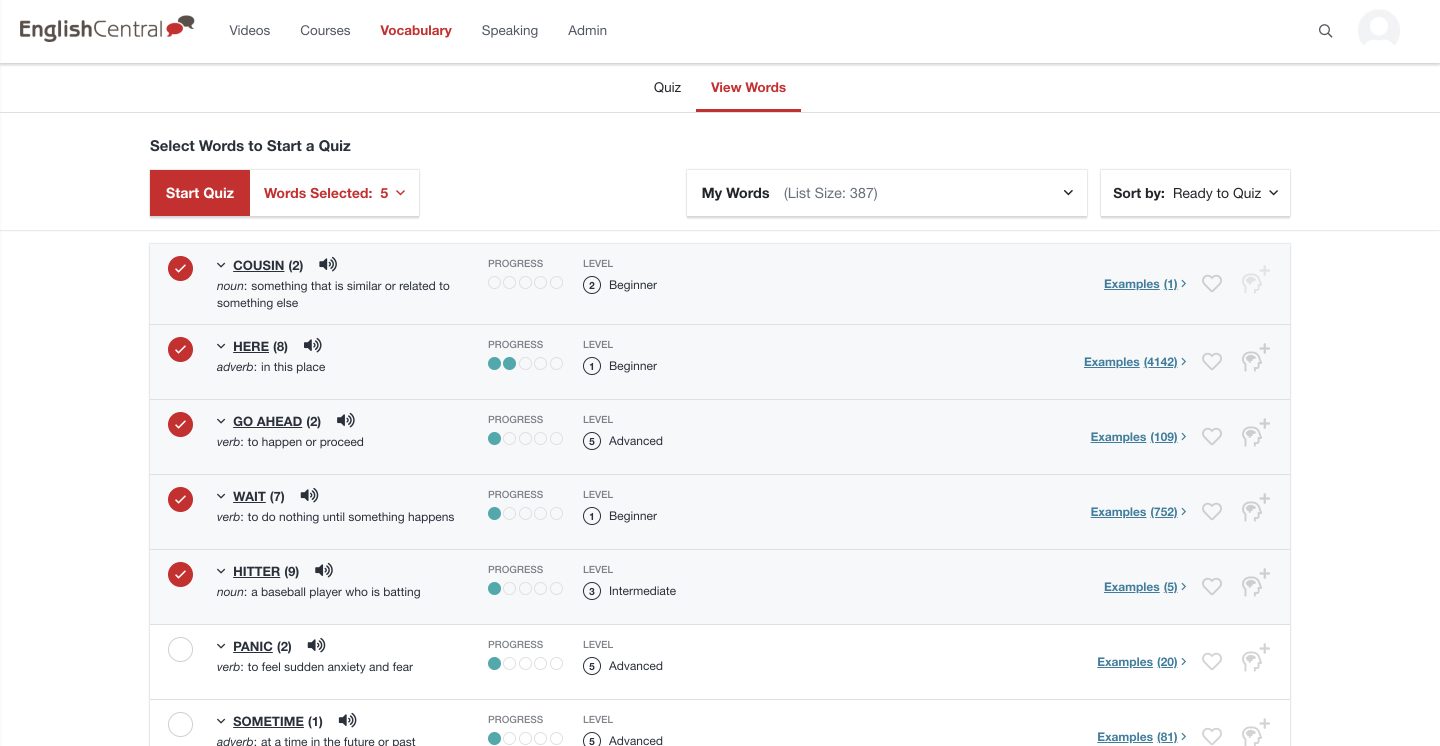

Furthermore, and very innovatively, a student can use the vocabulary presented in the videos to develop an individualized word list and take short quizzes on the words, at spaced intervals, to achieve long-term recall. This approach to learning vocabulary is much more effective and efficient than the traditional approach to teaching vocabulary in a language classroom where the teacher instructs the whole class on the same words regardless of which words each student may already know. Figure 3 shows a student’s access of “My Words”, charting the number of times the student has taken a quiz on the different words, the difficulty level of each word, and videos in which the word appears.

Figure 3

My Words

EC’s vocabulary learning component is built on research into high frequency word lists drawn from the English corpora. Browne et al. (2013) analyzed the 2-billion-word Cambridge English Corpus (CEC) to develop the New General Service List (NGSL) of 2,800 high frequency English words. EC employs this list as its core vocabulary of which 960 words are very high frequency academic words (e.g., distribution, impact), 1,200 are essential for TOEIC test takers (e.g., client, conference), and 1,700 words are high frequency business words (e.g., equity, goods). EC claims that students learning their core vocabulary will understand 92% of the words they are likely to encounter in print media, TV shows, movies, or daily speech.

Not surprisingly, EC has a very robust appeal to individual learners who access EC’s self-study modules on vocabulary learning and TOEIC test preparation on their smart phones. These users, particularly the corporate ones, can purchase an additional service, EC’s GoLive feature, where students schedule Zoom lessons with a real tutor coaching them on pronunciation, stress, pitch, and prosodics.

For teachers and program administrators, EC offers a very sophisticated learning management system (LMS) that enables them to set class goals and track student engagement. A teacher or program administrator can use EC as the listening, speaking, or vocabulary component of a course. Also, a teacher can tailor EC to fit a course theme by choosing the videos that are available for student viewing. A teacher can assign student use of EC the way that teachers once assigned students time in language laboratories. The major difference is that this listening and speaking practice is far more interesting and efficient compared to the old approach. The teacher sets weekly and term performance goals and gives marks for achieving them. These assignments can be easily adjusted for groups of different ages, needs, abilities, and motivation (e.g., by weighting listening more than speaking and vocabulary).

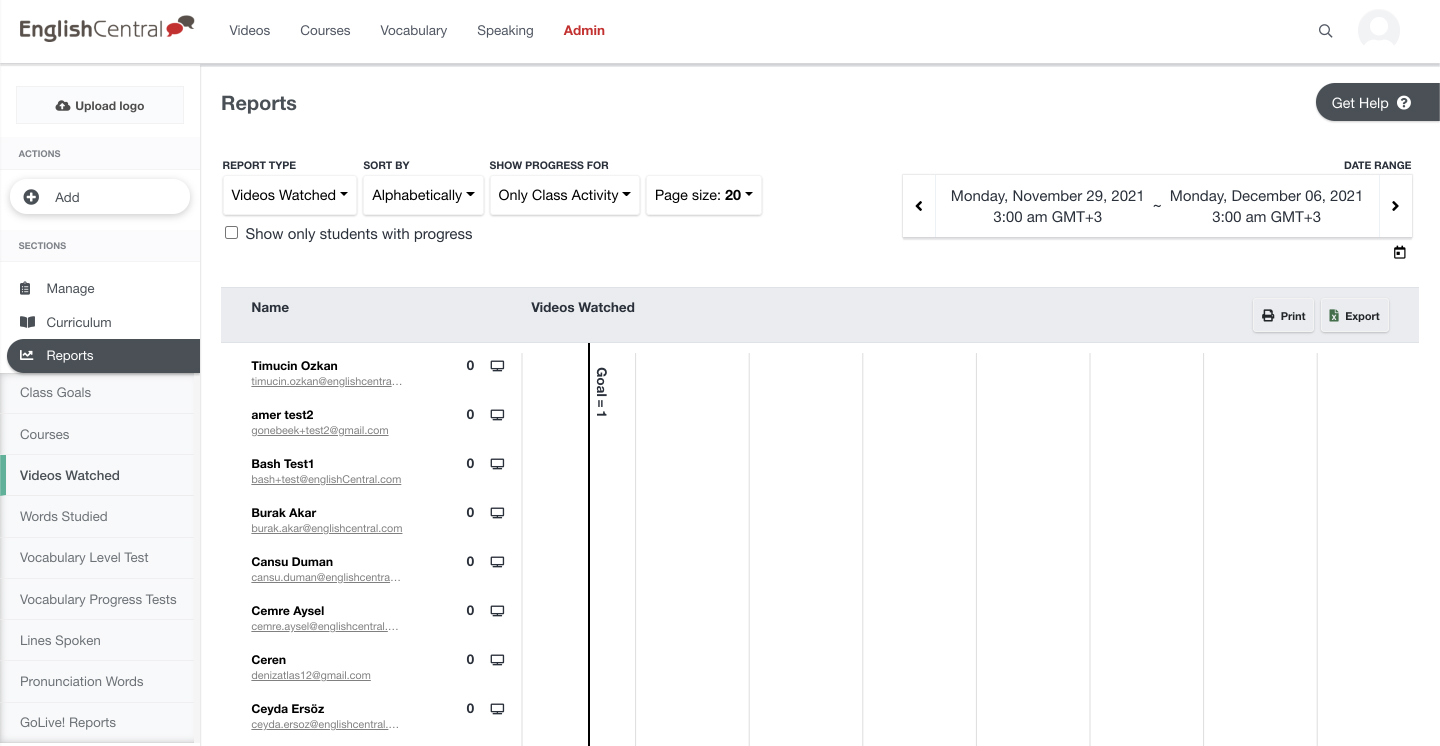

The LMS shows the videos that each student has watched, the time each student has spent listening, the vocabulary items that the student learned, the number of lines that the student has spoken, the student’s overall progress towards meeting the course goals, and a comparison of each student to their classmates in listening, vocabulary learning, speaking, and attaining course goals. Teachers can also use the LMS to message whole classes or to email individual students.

Figure 4 shows part of a class list with the students’ names redacted. The teacher can see each student’s progress toward achieving the course goal of watching 71 videos. In addition, the teacher can view the individual videos a student has watched or peruse a student’s list of vocabulary words. Just as easily, the teacher also can check the number of lines that a particular student has spoken and listen to recordings of each line by clicking an icon. At the term’s end, EC provides teachers with downloadable class PDFs for ease of grading.

Figure 4

Videos Watched

Recently, EC improved their interface so that a student logging on gets recommended videos based on their listening history and suggested daily goals. EC’s beta version, released in North America, transcribes students’ speech, shows the transcription to students, and provides further conversational prompts. Impressively, the EC platform is moving toward interactive speech like Siri or Google where student input will generate automated responses, simulating the interaction of a real conversation.

At present, EC includes videos for younger learners and some videos specifically created to teach English pronunciation and grammar. Videos for the latter two categories include, for instance, the “l and r” difficulty that Japanese speakers face in speaking English and grammatical points such as adjective ordering in English. By offering these traditional types of video offerings in addition to its authentic videos, EC is no doubt responding to a growing and varied consumer base. According to the EC website, 1,050 schools and businesses and 10,012,400 learners use it worldwide. Besides English and Japanese, the website supports nine other languages, including Korean, Turkish, and French. Like most CLPs these days, EC operates with a subscription model whereby students buy a monthly, school term, or annual subscription. EC also offers institutional pricing so that the cost per student for a term is roughly the price of a textbook.

Interestingly, one of the great strengths of EC also constitutes a weakness. It is extremely convenient to access the EC website via smart phones, but it is not as easy to read text on a smart phone as it would be while working on a tablet or a laptop. Second, although students can access the website anywhere and at any time on their phones, this can be problematic for some. They may feel embarrassed about speaking into their phones on public transportation and practicing English. In addition, students are often ambivalent about employing their smart phones which are so much a part of their social networks for educational purposes. Some students will no doubt worry about exceeding their data plans. Finally, students often use their smart phones in class for texting, reading e-mails, and surfing the Internet and may find it hard to stay on task and do their school work.

Finally, as with integrating any computer-assisted instruction (CAI) into a classroom or using it as part of a course, teachers will need to thoroughly understand how EC works before teaching with it. EC’s versatility and its many features mean that learning how to use EC effectively might take time. Teachers also need to provide their students with a good orientation to EC’s features, perhaps by introducing them to EC in the first class of the term and then, in subsequent classes, providing class time for reviewing its features and trouble-shooting any problems that students might experience. Even with EC’s high interest videos, students will need frequent teacher encouragement to meet their weekly targets. Teachers might take time at the beginning of each lesson to review the class’s progress, perhaps highlighting the work of higher scoring students (without using their names or identifying them), or finding time during class to coach individual students who are falling behind.

Altogether though, EC represents a significant development in CAI, an example that will encourage other companies to create innovative educational technology. The use of so much authentic material in this program is commendable, particularly if used with adult learners who will appreciate its relevance to their lives. EC’s potential for teaching vocabulary is remarkable and unlike anything else available on CLPs today. Likewise, the technology it uses for speaking practice is very useful and its future development worth following. Those educators interested in this powerful, innovative learning platform should visit the EC website to explore its various features and affordances for L2 instruction.

Browne, C., Culligan, B., & Phillips, J. (2013). The New General Service List. New General Service List Project. http://www.newgeneralservicelist.org

About the Author

Gregory Strong, English Department professor and language coordinator at Aoyama Gakuin University, Tokyo for the past 26 years, now works as an educational consultant with research interests in curriculum design and faculty development. His numerous publications include chapters in various TESOL books, a biography, works of fiction, and graded readers.

Email: gregstrongtokyo@gmail.com

You may also download the PDF version here

Hello and Welcome! My name is Gordon Bateson.

Hello and Welcome! My name is Gordon Bateson.

Leave a Reply